Pompeii, Italy

Roman history preserved by a volcanic eruption in AD 79

Editorial note: My wife, Jane, and I participated on a two-week Road Scholar tour, entitled "Beyond the View: The Amalfi Coast and Sorrento," during the summer of 2018. As an integral part of this tour, we spent a day in each of the following locations: Pompeii, Herculaneum, Paestum, and the Naples Archaeological Museum. All the photographs that follow were either taken by myself or by Jane on this trip, except for one, which was taken by me on an a trip in 1971, when we briefly visited the Pompeii site, but not any of the other locations.

Some useful geological context: The present volcano we see in the photographs is named Mt. Vesuvius. It is located in a caldera (a large crater) that was formed when a previous volcano at the same site, named Mt. Somma, erupted with sufficient force to destroy itself, collapse, and form the caldera. Volcanoes at this location have had this kind of major eruption about once every 2,000 years. It was called Mt. Somma before the AD 79 eruption that buried Herculaneum and Pompeii and formed the present caldera in which the current Mt. Vesuvius has been growing through episodic smaller eruptions. But the record of the surrounding rocks reveals that before Mt. Somma, an even bigger eruption occurred at about 1,780 BCE, and there were other previous major eruptions in the same location at about 6,000 BCE, 9,400 BCE, 13,000 BCE 15,000 BCE, 20,500 BCE and 23,000 BCE. Thus, there might be some ambiguity in what name we should use for the volcano, depending on whether it is before and/or after the AD 79 eruption.

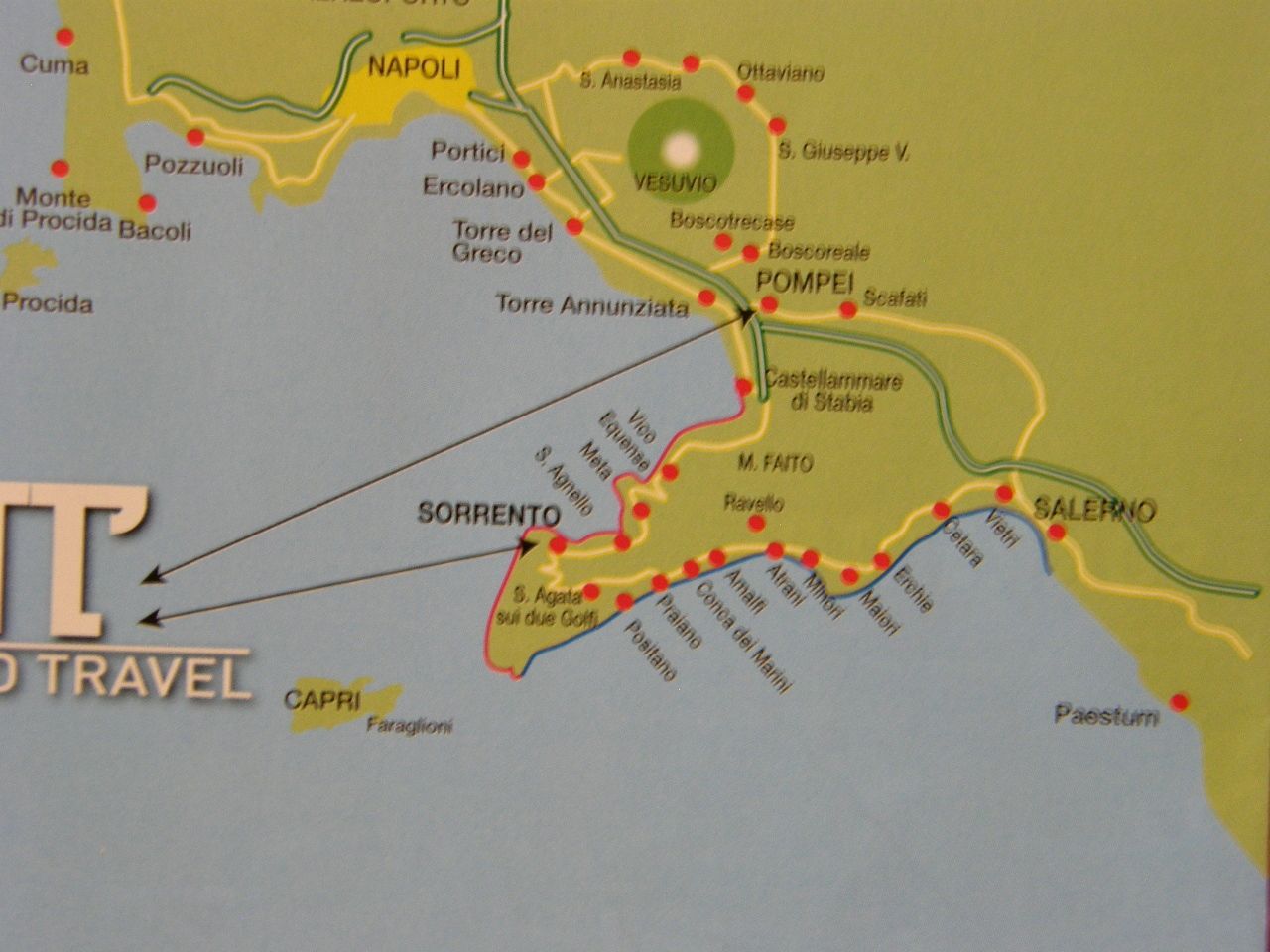

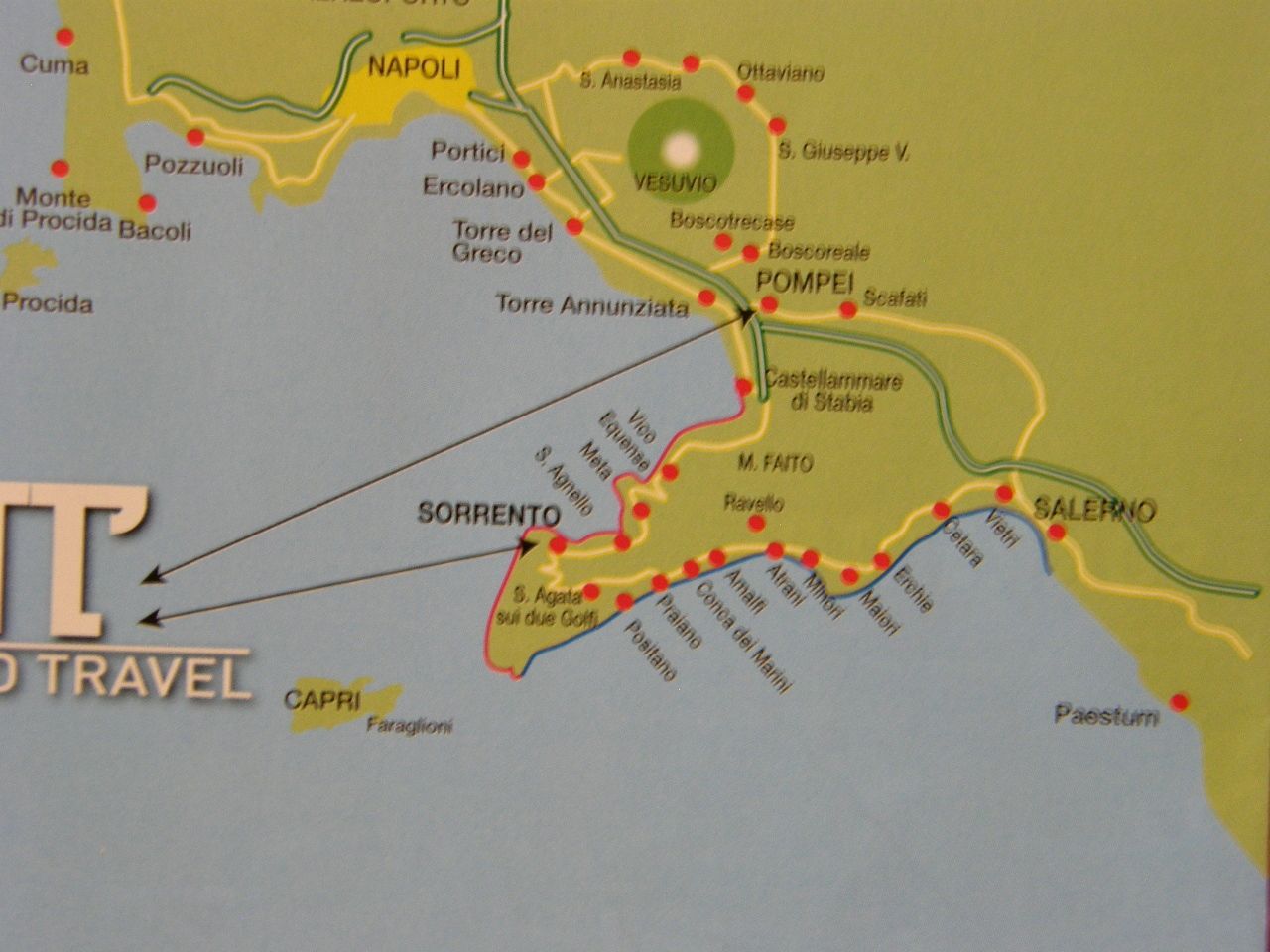

As can be seen on the map above, Pompeii is located a few miles southeast of Vesuvius volcano, which is the post-AD 79 volcano that progressively grew up in the eruptive crater (caldera) left by the eruption of the former, and larger, Mt. Somma. At about the time of the eruption of Mt. Somma, Pompeii was a sprawling and prosperous Roman town of about 10 thousand to 12 thousand inhabitants, about a third of whom were slaves. In AD 62 a large earthquake struck the area and caused extensive damage to many of the homes and structures within the entire region, Pompeii included. When the city was buried in ash by the eruption of Mt. Somma in AD 79, many of the earthquake repairs were not yet completed.

The above floor model and (sideways) wall model of Pompeii show the road pattern and neighborhoods within the city walls. Notice the stadium at the far end of the model, with a rectangular training field for athletes and gladiators right next to it.

Above is a commercial aerial photograph of the Pompeii excavation site. About 2/3 of the city has been exposed by the excavations over the last 300 years; the remaining 1/3 still is buried under layers of volcanic ash.

These air-fall deposits accumulated to progressively greater thicknesses on the roofs of the homes and other buildings, causing the roofs to collapse into the building interiors. Many people fled during the early hours of the eruption, but for those 2000 or so that remained behind their fate was sealed by the high temperatures and toxic gases of the rapidly-accumulating ash deposits and, if not that, as a final blow, by several pyroclastic flows of superheated ash and gas that flowed down the steep slopes of the erupting volcano at speeds in excess of 100 miles per hour. These people died in place and were covered over. During the two-day eruptive period, about 80 feet of ash and volcanic debris accumulated at the Pompeii site, burying the bodies, which over time decomposed and left skeletons in voids within the finer ash deposits. These fine ash deposits retained the shapes of the victims' bodies, including details about their clothes and, in some cases, even the expressions on their faces. When excavating, if a void was encountered, plaster or some other material was poured or pumped into the void and, after hardening, the ash was removed from around it, leaving a cast in the shape of the void. This plaster cast contained the bones of the victims. The image below shows a poster of the process; the other images show the results that are on display at the Pompeii site.

There was only one cast of a dog (the image above). It was chained and could not flee as the other dogs certainly did.

The image below shows a portion of the city wall, which at the time of the eruption would have enclosed the entire city.

The next three images (below) show the amphitheater which could seat 20,000 spectators. The floor was covered with sand to soak up the blood of the animals and people who were used and slaughtered for sport and entertainment, gladiators included. It was also used for public executions. The amphitheater was damaged in the large earthquake of AD 62, so some wooden seats substituted for stone seats, and the present images show existing seating only in the stone-seating sections and a somewhat smoother grassy surface where the wooden seats had been.

The next two images (below) show an entertainment complex of fields for athletic training and competitions and a theater for public performances.

In the above images, the small cells at ground level held gladiators. The open-air theater is in the distance.

Above is an image of the audience section of the open-air theater.

Pompeii was a thriving city nearer to the ocean than it is today due to the land added by the AD 79 eruption. Previous eruptions created deposits that made for a very fertile surrounding farmland. Thus, Pompeii was a city with integrated functions and a populace that spanned the range of very wealthy to poor and, even poorer, a large slave population. The city streets, as can be see in the following two images (below), show stone-floored streets with walkways on both sides. Horses pulled carts on the streets, the wheels of which wore grooves into the stone base. It is not hard to imagine that there was probably abundant horse manure that accumulated in the lower streets between the higher walkways on each side. Thus, there are periodic stone steps to walk from one side of the street to the other without necessarily getting your feet messy in the process. The spacing between these stepping stones determined the spacing of the wagon wheels and carriage wheels.

The two images that follow (below) show stones for grinding (milling) grain and the oven for baking bread in an integrated bakery shop.

Below is a restaurant with a counter that contains inserted large jars that could hold solid foods or liquid soups or drinks. There are many of these in Pompeii and also in Herculaneum. They all seem to have counter surfaces that are composed of hand-sized slabs of stones that have varied compositions and appearances. These small slabs probably come from many different distant locations. I suppose each era has its preferred fashion.

The next two images (below) show wall murals from wealthy estates within the city.

The image below shows the elaborate wall and ceiling decorations of a bathhouse.

The following view (below) shows the present Mt. Vesuvius, which has been growing in the crater (caldera) of the former Mt. Somma, about 5 miles away. In the forground are some pillars from the municipal parts of the city center, with a surviving sundial on the nearer pillar.

The image below shows a painted fresco that is thought to be a rendering of Mt. Somma prior to its AD 79 eruption. This fresco was found in Pompeii and is presently on display in the Archeological Museum of Naples. Based on this image, Mt. Somma would have been taller and steeper than the present Mt. Vesuvius. Mt. Somma would have formed in a previous caldera, formed by a violent eruption of a preexisting volcano in 1780 BCE, during the interval between then and 79 AD.

Addendium: It is reported that Pompeii now receives about 3 million visitors per year. What differences do Jane and I notice between our visits to Pompeii in 1971 and 2018? Certainly the crouds are now bigger, although the restored site is bigger too. At neither time were we able to see more than a small percentage of the whole of the restored area. A small but maybe interesting difference sticks in our minds: in 1971 there was a yellow (volcanic?) dust sufficiently spread along roads and ruin surfaces that outside the exit gates there were locals who, for a small price, offered the service of washing the yellow dust off your feet and/or shoes/sandals. Whether this dust was from the volcanic ash that was being excavated or whether it was dust blown in from elsewhere -- we will never know. But today there is no need for these foot-washing services because there doesn't seem to be any yellow dust on the roads or among the ruins that can be visited. In retrospect, the yellow dust added to the tactile authenticity of the earlier experience.

A Second Addendum: I took the image below on 35mm color transparency film (a "slide" used for classroom projection) in 1971. I include it here because, ironically, it shows better than my more recent images the edge of the original Mt. Somma to the right of the Mt. Vesuvius summit and slopes. My more recent images also show this feature, but not without some foreground object obscuring an important portion of the more distant view. I digitized my 35 mm color slide and present this digitized version in this web image.

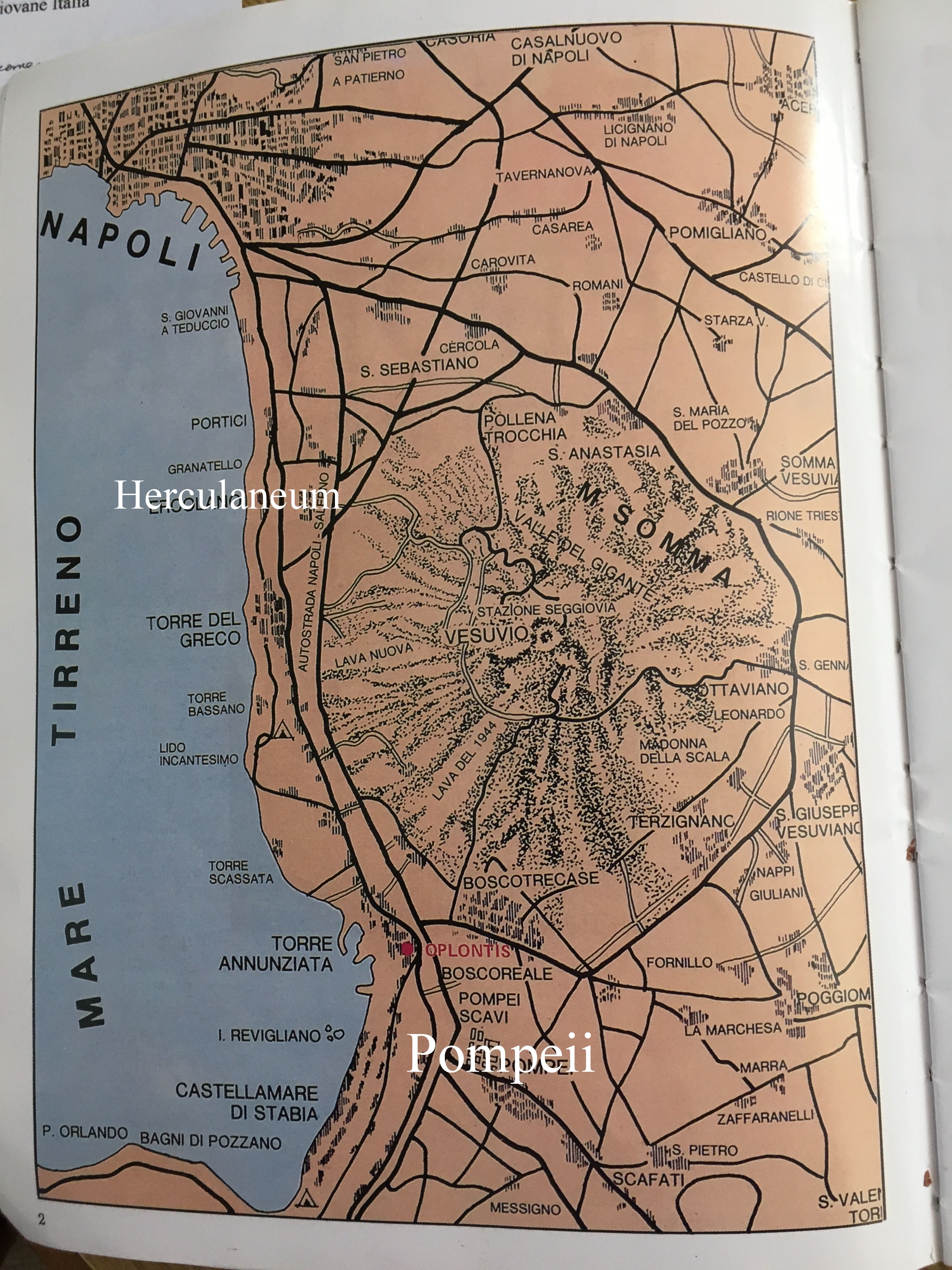

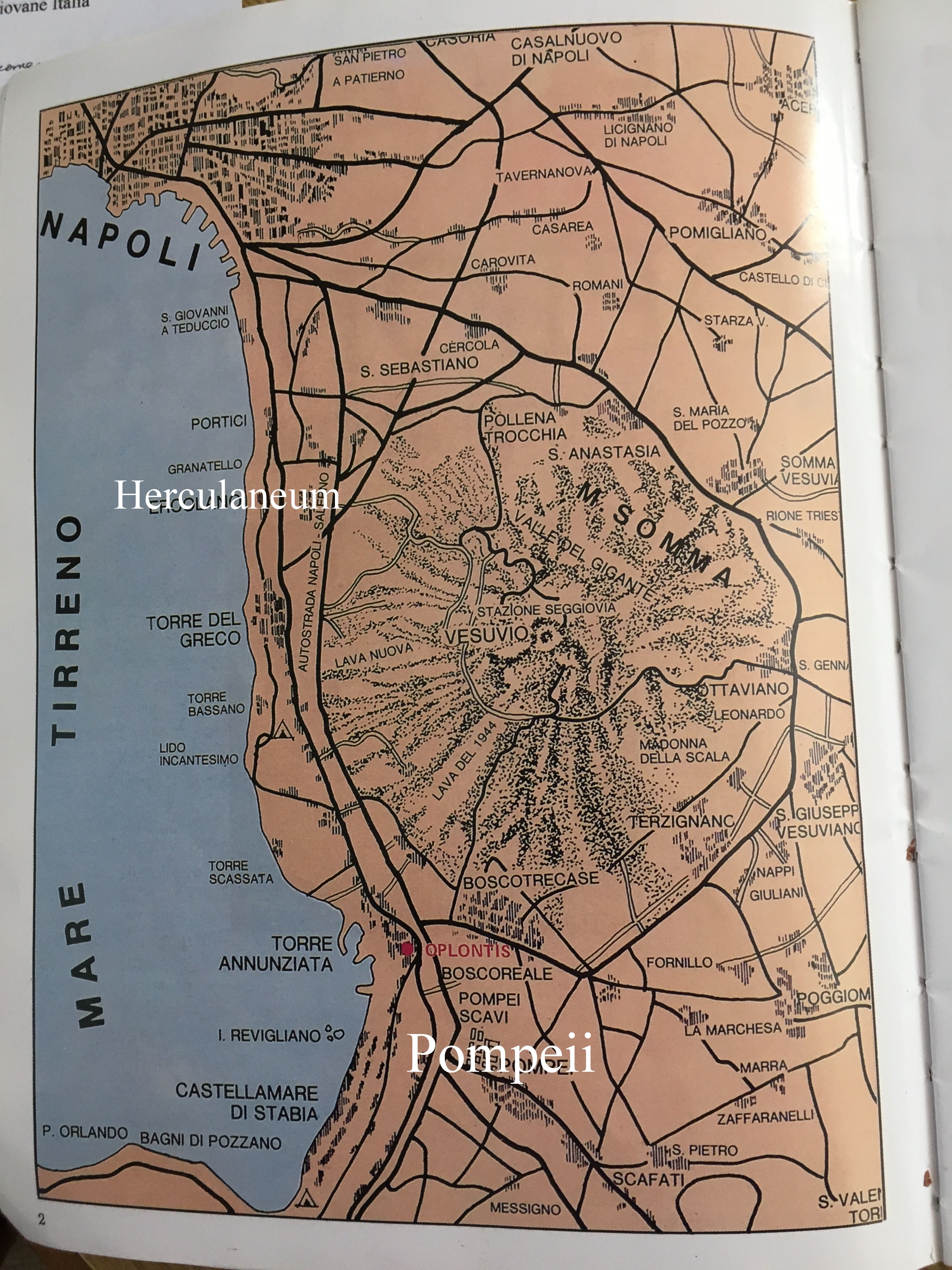

The map below shows the summit caldera of Mt. Somma with the newer Mt. Vesuvius having partially filled its western side, leaving the slopes of the original Mt. Somma on the northeastern and eastern sides. As seen from Pompeii, which is only 5 miles south of this volcanic feature, the perspective for the above image can be visualized.

I end this section with a map that shows the proximity of ancient towns to the Mt. Vesuvius-Mt. Somma volcano. If this volcano were to erupt today to the same extent as it did in AD 79, the estimate is that 200 thousand people would die if no evacuation were to occur. If it were to erupt as it did in 1780 BCE, and if no evacuation occurred, then all of modern Naples, with three million inhabitants, would be wiped out, because that was a much larger eruption. Consequently, this volcano is one of the most intensively monitored on earth.

For additional information about the geology of this region and details about the volcanic eruptions of Mt. Somma / Mt. Vesuvius, see the following:

(below) Somma Vesuvius: the Volcano and the Observatory. Field trip guidebook.

(below) Pyroclastic flow hazard assessment at Somma-Vesuvius based on the geological record.

(below) Pompeii and Herculaneum and eruptions of Vesuvius.

(below) Impact of the AD 79 explosive eruption on Pompeii, I. Relations amongst the depositional mechanisms of the pyroclastic products, the framework of the buildings and the associated destructive events.

(below) Impact of the AD 79 explosive eruption on Pompeii, II. Causes of death of the inhabitants inferred by stratigraphic analysis and aerial distribution of the human casualities.

(below) Lethal Thermal Impact at Periphery of Pyroclastic Surges: Evidences at Pompeii.